Being a computer engineer is neither illegal not immoral. It isn’t even something to be ashamed of, I guess, but there was a time in my life when I was reluctant to admit that I was one. The confession created all sorts of problems. Consider, for example, the simple, friendly ritual of meeting people at a cocktail party. A standard part of the ceremonial is to be asked, ‘And what do you do?’ The simple response, ‘I design digital computers’, usually turned out to have a dramatically chilling effect.

After a promising start to the Prologue, things go very askew. This was published in 1977, so there is absolutely no excuse for what follows:

In fact, some of my best friends are computer engineers, and I wouldn’t really mind if my daughter married one.

The rest of the book continues a melange of sometimes pithy but often quaint observations, technical explanation, gripes at colleagues, reactionary comments about gender… but sprinkled amongst these are some astute reckonings, some of which temper the sexism elsewhere. There is a general distrust of utilitarianism – or rather, the arithmetic of the good. In the chapter An Emotional Appeal, the author makes an argument for replacing human names with numbers that trades on the promise to end discrimination by ethnicity or gender, the ability to finely specify one’s marital status (‘0 could mean single and happy that way, 2 could mean married but looking, and so on up to 9, meaning none of your business.’) and to establish family relationhips by choice rather than circumstance, etc. But the logic doesn’t move him – he simply prefers that people have names rather than numbers. Here’s the end of the last chapter, Looking Ahead:

The danger is that we will come to see [the computer], not as a model of the way that people do think, which it isn’t, but as a model of the way that people should think, which it must never become. The hazard is not that we have made it in our image but that we may try to remake ourselves in its image.

With the power to give us practically unlimited logical capability, the computer is a machine of the greatest significance. Don’t ever understimate it. But human intelligence goes beyond logic and it is the other components of thinking that separate people from computers. Use them or lose them.

___

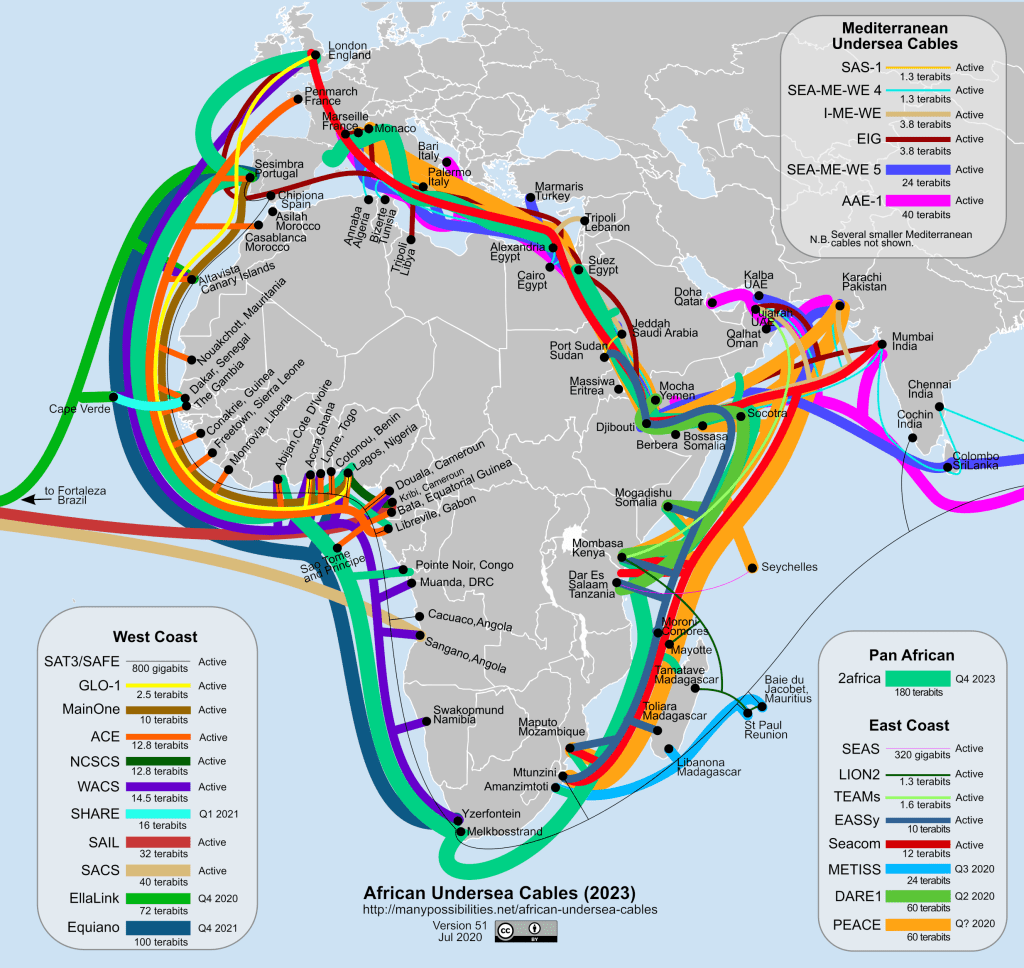

African Undersea Cables (v.51, July 2020) map by Steve Song (cc-attrib-4.0)

African Undersea Cables (v.51, July 2020) map by Steve Song (cc-attrib-4.0)